‘90s

Welcome back! I hope you’re buckled in because there’s a lot to cover in this decade. In the last two decades, we saw CCA establish itself as a prominent voice in air quality issues in California. The ‘90s continues the story of the fallout from Abramowitz vs. EPA and brings new leadership, renewed energy, and a host of accomplishments. Throughout this decade, the weight of the complexity of air quality improvement starts to set in and we start to see that this isn’t a problem that can be solved with the snap of a finger. It becomes obvious that, to fix air quality, it’s going to take coalitions of people coming together and working steadily over time to move the needle, and we might even have to work with our opposition to make it happen.

The Son of Abramowitz

We last left off at the resolution of Abramowitz vs. EPA – the EPA agreed to explore a settlement with Mark. They had two sticking points: 1) a refusal to acknowledge oxides of nitrogen as a precursor to ozone, and 2) federally controlled sources, like ships. Mark agreed to these points, “not wanting the perfect to be the enemy of the good”, but it didn’t matter because the EPA reneged on the settlement agreement anyways. In the end, the court ruled in favor of Mark and required the EPA to reject South Coast AQMD’s air quality plan for the South Coast basin.

As a follow-up, Mark, under the aegis of the Coalition for Clean Air, filed a second lawsuit, which became known as the “Son of Abramowitz,” to force the EPA to create a Federal Implementation Plan, since the State had failed to do so. In Mark’s words, “This case was easily won, too, and the EPA was forced to prepare its own plan for the region”. With another victory, we close out the story of the Abramowitz vs. EPA, but there’s still much to tell in the aftermath.

New Leadership, New Energy

A Santa Monica city council member and former mayor named Denny Zane had spent the previous decade advocating for alternative fuel use in Santa Monica and cared deeply about environmental issues in the city he served. In his words, it had “become part of [his] mission as a council member to help the city build a commitment to clean technologies.” As a member of the Tom Hayden and Jane Fonda Campaign for Economic Democracy, Denny and various associates of the Coalition for Clean Air orbited one another’s circles. Board members Abby Arnold, Cliff Gladstein, and Tom Soto all worked directly on Tom Hayden’s Senate campaign with Denny. After the 2nd or 3rd interview for this series, I certainly started to get the “oh wow, small world!” effect frequently.

In 1993, CCA hit another leadership snag: they hired someone as Executive Director who had an unfortunate family emergency and needed to step down. The CCA Board of Directors approached Denny, who was interested in building a work life apart from his political life and asked him to step in as interim Director, “just for the summer”.

Mere days into Denny’s role as Executive Director, the courts ruled in favor of the Coalition for Clean Air in the Son of Abramowitz lawsuit. It was an exciting and huge moment for CCA that Denny Zane met with excitement and zeal. Denny, on behalf of CCA, was responsible for negotiating with the EPA to develop a Federal Implementation Plan (FIP) for Southern California to meet its air quality goals.

Denny got to work doing what we at CCA do best: building coalitions and networks of people to come together and figure out how to move forward. With Mary Nichols, air quality icon, representing the EPA along with Cecilia Estolano, CCA staff member Linda Waade got to work building a plan that would get the South Coast region into attainment.

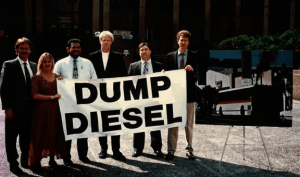

Dump Diesel, Part 1

Dump Diesel, a foundational campaign for CCA throughout the ‘90s and early 2000s, was a rallying cry to Californians to work with CCA to get rid of the fuel that was ruining our air and affecting our health. Dump Diesel led to natural gas public transit approval in Los Angeles; the Carl Moyer Program, which aims to reduce emissions from school buses; and a lawsuit against grocers, which you’ll learn about in the next blog.

Dump Diesel continued to be a key CCA campaign. Denny Zane moved on and Linda Waade took over as Executive Director, with future E.D. Tim Carmichael as second-in-command. Linda got to work increasing CCA’s media presence including a series of debates on public access television highlighting CCA’s work and bringing air quality debates into people’s homes.

[row]

[col span=”1/3″]

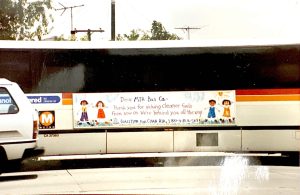

MTA Buses

A major accomplishment under Denny’s leadership includes a huge victory with the Metropolitan Transit Authority of Los Angeles. MTA had purchased methanol buses that just weren’t working out. The methanol was corrosive and damaging the buses in an unsustainable way. So, the plan was to go back to diesel. After all, there just weren’t that many alternative fuel options. Cindy and Alan Horne, CCA Board Members and Entertainment Industry mainstays, called Denny up to tell him that MTA was planning to go back to diesel, and that we needed to do something about it.

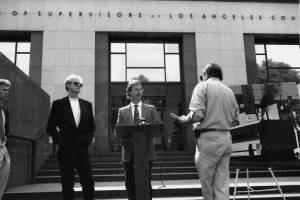

Who did Denny call? Everyone’s favorite environmental advocate and CCA Board Member, Ed Begley, Jr. Ed Begley, Jr.’s voice was and is highly respected, especially on environmental issues. Denny mobilized Ed, Tim Carmichael and other CCA staff to testify at the MTA committee. Richard Alatorre was committee chair and Antonio Villaraigosa was a committee member. Ed Begley, Jr. and the rest of the CCA team made an impassioned case for not going back to diesel, and to try natural gas instead.

After their pitch, Denny tells me, “Villaraigosa turns to Alatorre and says, ‘we’ve got to do this’.” As it turned out, the staff at MTA was deeply divided on the issue. Some felt that public transit itself did enough to reduce emissions, while others had been learning about natural gas and felt passionately that natural gas was worth a try. The issue was contentious, but Ed Begley and CCA’s argument tipped the scales, and natural gas buses rolled into Los Angeles.

Trucking and Shipping

As Denny dug deeper into the air quality issue in California, and the best approach to solving it, he became more and more certain that heavy duty trucks needed to be the focus of our efforts to improve air quality.

Denny worked with Stephanie Williams, a labor lobbyist who was initially quite resistant to air quality advocates. Over time (and a couple drinks, according to Denny) he was able to win her over and show that they weren’t interested in hurting “mom-and-pop” truckers, in fact, quite the opposite. These mom-and-pop truckers were more at risk of the consequences of poor air quality, and they deserved to have their health protected. The same remains true today.

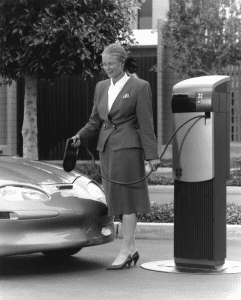

With Stephanie Williams now on board, Denny, Stephanie, and Mark Pisano at Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) started Trucking and Shipping Working Groups designed to discuss these issues, their effect on air quality, and what can be done that still protects the interests of the port workers and truckers. Eventually, they landed on the plan to create an incentive, a pot of money for alternative fuels that would provide the investment necessary to get diesel off the roads in California. At the time, natural gas was the leading option.

Denny felt strongly that solving this issue was the top priority. But the Board at CCA didn’t want the organization to get too focused on one issue. During our conversation, Denny shared with me that at the time he understood, “but I need to focus on trucks, because that is where my heart and my head tells me needs to be the priority”. This is something that I really admire about not only Denny, but many of the people that have come through the Coalition for Clean Air. They’re not in it for money, or clout, or a cushy job, they’re in it because they believe in the work. It can be a thankless job, but they want to make a difference, so they commit themselves fully.

The Carl Moyer Program

At this point, Denny flies up to Sacramento on his own dime to get to work. He’s introduced to

Carl Moyer who he describes as a sort of Willie Nelson look-a-like, with a long beard and a gravelly Southern twang. Denny speaks about Carl Moyer with affection and respect. Carl Moyer was, after all, “by all accounts, the diesel expert”. V. John White, Speaker of the Assembly Antonio Villaraigosa, and Jim Brulte worked together to create a bill that would set aside money specifically for getting heavy duty trucks to switch from diesel to alternative fuels. And it was a success. The bill, which set aside $25 million in alternative fuel funding, passed and was signed into law in December of 1998, set to go into effect starting January 1, 1999.

During that short time, the unthinkable happened. Carl Moyer, while on a skiing trip with his family, had a heart attack and died on the slopes. As you can imagine, the impact of losing such a bright leader was devastating. He was the mind behind this bill that Denny considers “one of the single most significant clean air programs the Air Resources Board ever adopted”. In his memory, the Governor named the bill the Carl Moyer program, which it is still known as today.

The RECLAIM Program

It would be impossible to talk about air quality or environmental issues in the 90’s without discussing RECLAIM, or the Regional Clean Air Market. Throughout the success of this decade, the development of RECLAIM was happening in the background and it is a definitive program in the relationship between air quality improvement and the private sector. RECLAIM is complex and highly controversial. Even within CCA, there were widely differing opinions. Some believed that a path had to be created to get industry on board, some way for them to effectively improve. Others believed that this specific program just wouldn’t result in actual progress.

RECLAIM is essentially a cap-and-trade program designed to give the largest stationary source polluters (i.e. factories, businesses, etc.) a pollution “cap”. I like to think of it as a token that represents a certain number of allowable emissions for the organization in possession of the token. From there, companies that have more tokens than they need to conduct business can sell those tokens in a marketplace, and large organizations that need more tokens to cover their emissions can then buy those tokens to allow them to be in compliance with the law, while still emitting pollutants at the level “necessary” for them to keep their businesses growing. The plan during this time was to lower the amount of overall emissions allowed, thus reducing the total number of “tokens” available, and eventually get all businesses in California to reduce down to zero-emission.

At the time, the concept was considered groundbreaking by many. It promised real progress in the emissions issue. However, issues arose. Ultimately, it allowed big polluters to just continue business as usual and it did nothing to address the concerns of environmental justice advocates. Local communities were still paying the price, especially underrepresented poor neighborhoods and communities of color, and businesses weren’t being forced to reduce their emissions. The focus on cumulative emissions statewide wasn’t addressing the public health crisis that was impacting the day to day lives of Californians.

The ‘90s

During this decade alone, CCA had 4 different Executive Directors. Going from Tim Little, to Denny Zane, Linda Waade and finally Tim Carmichael, the team had tremendous accomplishments and continued to shape the air quality conversation.