Welcome to the 21st century, you survived Y2k (again!). Two quick notes: 1) in the last blog, we mostly covered the legacy of Denny Zane, whose contribution has gone down in Los Angeles history. Tim Carmichael started as Executive Director in the late ‘90s and, therefore, should have started in that blog, I’m discussing CCA’s work under his leadership starting here. I appreciate your understanding of some of the timeline blurring between the ‘90s and ‘00s blogs. 2) These blogs are an abbreviated version of an exhaustive history of CCA. There are many other contributors to CCA’s legacy throughout the years whose stories and perspectives I haven’t been able to highlight with this series. So, as you’re reading, please know that there is much more to tell than what’s made it into these blogs.

Overview

At this point, CCA is a mature organization that’s been around for decades, had huge victories, and saw smog improve in real time. Our work had been focused on air quality exclusively, geographically focused on the Los Angeles Basin, and the organization’s lack of diversity reflected some hard realities of environmentalism as a whole: largely white, based in the westside of Los Angeles, and middle class. These are the three major points of pressure and change for CCA during this decade.

Climate Change

The turn of the century brought with it a hot new issue for everyone to be super stressed about: climate change. Talking about climate change with people who have given their lives and careers to environmental issues is a more careful conversation than I initially anticipated it to be. Everyone appreciates the urgency and global scale of the climate problem, but it’s a different ballgame than the more locally based, acute environmental issues that drove many of the campaigns that grew into the environmental movement.

The increase in conversation around climate change brought with it a renewed investment, monetary and emotional, in environmental concerns. However, there’s a sense that while climate change brought funding to air quality issues, it took away attention from other priorities. The air we breathe, the water we drink, the way land is developed, and the products we consume aren’t the same as massive changes to our climate globally. The two are related, of course, but we have to see the forest AND the trees, so to speak. And it’s important to understand the distinction as we discuss the fight for clean air in the 21st century.

Changing Course

Tim Carmichael was hired as the Executive Director starting in the second half of the ‘90s. He had been volunteering with CCA and was primed to step up into an organization preparing for the 21st century. Tim led CCA’s through a transformative period, where our scope of concern evolved to include climate change, expanded to focus on the entire state of California instead of just on the Los Angeles basin, and grew from 3 full time staff to 17.

In 2002, Tim Carmichael fell in love. Everything would have been perfect, except for the fact that she lived in Sacramento and CCA only had a Los Angeles office. If only remote work had existed! As he considered what to do, the idea to raise enough funding to open a Sacramento office came up. They would secure the funding necessary to open the office, but not without consequences.

Controversial Expansion

CCA had developed a strong reputation with foundations and funders by being honest, realistic, and most importantly, delivering results time and time again. Tim had solidified his relationship with a couple key folks at the Hewlett Foundation, namely Hal Harvey and Danielle Deane who came to really believe in what CCA could accomplish. Tim had big plans for CCA that included more staff, new offices, and getting engaged on more issues, like climate change.

The Hewlett Foundation offered CCA what Tim called a “monster grant” of $1,000,000 a year to support the foundation’s New Constituencies for the Environment program. The pushback was almost immediate. Internally, board members were concerned about having such a huge percentage of funding come from one source, and the implications that would have on CCA’s strategy as an organization. Externally, the pushback was much more intense. The environmental justice community, a collective term for a broad range of primarily locally based organizations and activists concerned with centering people of color and those living in poverty in environmental change conversations, was gaining influence in California. They were forcing decision-makers to account for the disproportionate impacts of pollution on the most disenfranchised and underserved communities. And they were understandably angry to see CCA, regarded as a white, chardonnay-sipping “Westside” organization, receiving such a huge amount of money.

The suggestion was made to re-grant the money to groups that were more closely involved in the environmental issues directly affecting the most vulnerable and polluted populations in Los Angeles. But Tim was concerned that if CCA became a funder, it would detract from our ability to do the advocacy work we were best at. So, he decided to use the money to build CCA and create equity internally by focusing on diverse hiring. As CCA made this transition, a lot of time and resources went into internal issues, such as increasing the diversity of board members and staff, and hard decisions about strategic and policy advocacy priorities.

The trouble is rapid growth can be both a blessing and a curse for an organization. That money opened the Sacramento office that is still open today, as well as a Fresno office. It hired a full-time communications staff that exploded CCA’s media presence and got CCA into the news more than it had been before or since. It allowed more flexibility for staff to work on issues across California. But it also soured relationships with those who should be our greatest allies, those whose boots were on the ground, living with the reality of poor air quality every single day. It perpetuated the status quo that predominantly white, “insider” organizations will always be prioritized over the underserved communities suffering the most. It was a choice that helped CCA strengthen its position at the time, but it set us back in building the bridges and allyships that are key to uplifting those most in need and amplifying their voices.

The Pavley Bills

One afternoon, Tim Carmichael got a call from then-Assemblymember Fran Pavley. A small group called the Bluewater Network (now merged with Friends of the Earth) had pitched the idea for legislation that would focus on creating a comprehensive system to limit greenhouse gas emissions. This was right up CCA’s alley, and they got to work creating and sponsoring AB 1493, the Clean Cars Law. The law directed CARB to “adopt regulations that achieve the maximum feasible and cost effective reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from passenger vehicles.” California’s Clean Cars Law was the first in the nation to set standards regulating greenhouse gas emissions from cars, and and it led to a radical transformation of the auto industry.

Knowing that vehicle emissions were only the first step towards reining in California’s air problems and preventing climate change, Assemblymember Pavley wanted to go further. In 2005, she and Assemblymember Fabian Núñez introduced AB 32, the Global Warming Solutions Act. At first there was some hesitancy from the large national environmental organizations to support the bill. Tim Carmichael told me, “George Bush was in the White House, nothing [was] happening in Congress relative to the environment, the national organizations were freaking out saying ‘no, we can’t do a climate bill in California because it’ll take the wind out of the sails of us accomplishing the same in D.C.’” It was an uphill battle, but eventually, Sierra Club California and NRDC joined the ranks. CCA’s current Policy Director, Bill Magavern, who was working at Sierra Club at that time, told me that, when AB 32 was signed into law, “it was the most important climate law passed in the United States. Period.”

The bill, signed into law in 2006, required California to reduce all greenhouse gas emission to 1990 levels by 2020, an aggressive goal for the state. Ultimately, the goal of the bill was to mitigate risks associated with climate change through renewable energy resources, cleaner transportation, and improved energy efficiency. For the record, the state met that goal four years ahead of schedule.

Dump Diesel, Part 2

As I described in the ‘90s blog, Denny Zane started Dump Diesel, but Linda Waade and Tim Carmichael kept the torch lit. In the early 2000’s a young and ambitious Yale graduate named Todd Campbell became the Science and Policy Director at CCA. He took the Dump Diesel campaign and ran with it. Todd, a man who seems to have lived a million different lives, would go on to be the Mayor of Burbank, be a Board Member for several environmental organizations, including the California League of Conservation Voters (now known as California Environmental Voters), the Energy Coalition and more before settling into a career in the private sector working on alternative fuel sources. But in the year 2000, he was a CCA staff member, eager to improve air quality in California. In these years, the Dump Diesel campaign anchors around three primary initiatives: a report on diesel school buses, a grocery store lawsuit, and CCA’s perennial efforts to clean up California’s ports.

Dump Diesel: Don’t Kids Deserve Better?

One day, when Todd was heading into work, he noticed a crowded school bus and saw a “plume [of exhaust] that was egregious. It was amazing.” He just happened to have a company camera on him, realized he was going to be late, and decided to trail the bus instead. The picture he got that day sparked CCA to release a study in support of a rule the South Coast Air Quality Management District was considering that would require school bus fleets to transition to alternative fuel vehicles.

Through the study, they learned that, because the exhaust from the engine went from the front to the back underneath floorboard that were cracked and often leaked, kids on school buses were exposed to 80-100 times the acceptable risk of diesel fumes determined by the EPA. Todd’s goal with the report was to raise awareness and to pressure South Coast AQMD to pass the rule, and he succeeded.

Dump Diesel: The Stakeout

Looking for a way to raise public awareness of air quality issues in highly populated communities, CCA started looking at where freight trucking was having the biggest impact. They landed on grocery store distribution centers, which were often in the middle of underserved communities. They looked for locations where they could feasibly test diesel trucks’ impact on air quality without too much other traffic. They needed to prove that these dirty diesel trucks were having an impact on air quality and were in violation of the law.

So, it was time for a sting operation (of sorts). CCA teamed up with UCLA and set up vans equipped with air quality monitoring devices upwind and downwind of the grocery distribution centers, with cameras so they could verify truck counts. Todd Campbell slept in the vans 24 hours a day for 7 days straight. Except for one break for a much-needed shower. “I look back on it now and I just think to myself – I was nuts,” Todd told me. During his air quality stake out, Todd was mildly harassed by store workers and even had police come up to him and ask him if he was sure he wanted to be out there that late at night. It was grueling, but worth it. They filed a lawsuit against Ralphs/Kroger, Safeway, Stater Brothers, and Lucky Supermarkets, and it wrapped up very quickly. The grocery chains agreed to a settlement, which according to Todd, “created the largest heavy duty alternative fuel demonstration project anybody was able to achieve.”

Dump Diesel: The Port of Los Angeles

The Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are in a convoluted, seemingly never-ending battle between economic interests and community interests. It would be impossible to cover the entirety of the history of the Ports here, so I’ll be focusing on the lawsuit that CCA, NRDC, and local homeowners filed in 2001. Nicknamed ‘China Shipping’ this lawsuit never seems to end. In fact, more than 20 years later, we are still involved in litigation on this issue.

The Port of Los Angeles built a 174-acre terminal for China Shipping Holding Co. Community members living around the two ports were outraged – the terminal would bring a significant increase of diesel exhaust into the community of San Pedro without an environmental review. CCA, represented by NRDC, partnered with local homeowners groups, to file a lawsuit, which the California Attorney General joined. The lawsuit against the Port of Los Angeles sought to force the port to do an environmental review and make the new terminal safe for the community to live nearby.

Settlement negotiations were brutal and any of the mitigating measures that were presented to the Port were met with resistance. One suggested measure was to have ships use what is called “cold ironing,” essentially having ships “plug-in” to receive electrical power at berth instead of running their engines on bunker fuel while at dock. The Port of Los Angeles felt they were receiving far too many containers to have time for a plug-in process. Todd called a friend in the military to see if they used cold ironing, and if so, when they started. World War II, his friend responded. Somehow battleships in the midst of war have time for cold ironing, but not a container terminal? Needless to say, they were able to win that measure in the final settlement.

After an appellate court victory, the parties reached a settlement. It included $50 million in total that would be spent on electrifying the China Shipping terminal, including requiring cold ironing, reducing emissions from non-road equipment, like cranes, creating a traffic plan for the terminal, incentives for alternative fuel heavy duty trucks driving in and out of the Port, community benefit projects, and to create a plan to reduce emissions from the Port.

It was a huge victory for CCA. Everyone believed that this was going to have a major impact, making the communities around the port a safer and healthier place to be. Unfortunately, it didn’t quite turn out that way, but we’ll tell more about that story in our next blog.

Danger at the Dry Cleaners

One of the largest accomplishments from this decade was CCA’s work behind getting the toxin perchloroethylene banned from use at dry cleaners. The toxin was determined to be a known cancer-causing chemical. It was noxious and affected the air quality and health of those that worked in and lived around dry cleaners, not to mention the people wearing dry-cleaned clothes!

The team at CCA got to work creating a report to raise public awareness through a media blitz and put pressure on the South Coast AQMD to vote to phase out “perc.” They were met with resistance from the dry-cleaning industry, but ultimately, the effects of the toxin on human health were too severe and the AQMD voted to phase out all use of perchloroethylene as the equipment was replaced but no later than 2019. California became the first state in the nation to fully ban the use of perchloroethylene in dry cleaning.

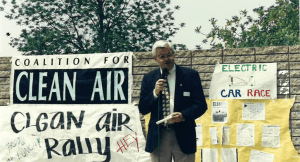

Fashion Shows

We’ve covered lawsuits, major legislative changes, and organizational shifts. Now, I hope you’ll indulge me in a fun project Todd Campbell worked on while at CCA. One thing I truly enjoy about Todd is that he’s dedicated and ambitious about air quality, but he’s also fun. The ability to perform a 24-hour-a-day stakeout to gather evidence for a lawsuit and hosting a fashion show for air quality perfectly encapsulates The Spectrum of Todd.

CCA had been working with a consultant to develop an event that would highlight environmentally-friendly fashion as an opportunity to bring Los Angeles environmental leaders and policy makers together. Todd frequented an Aveda store down the street from CCA’s Santa Monica office and made friends with a sales consultant there, who upon hearing about the event convinced Aveda to offer makeup and backstage services for charity.

(I have to be honest with you for just a moment – as fun as these fashion shows were, I just wanted an excuse to show you these amazing pictures.)

[row]

[col span=”1/3″]

A new direction, the hiring of Dr. Joe Lyou

As the first decade of the 21st century ended, Tim Carmichael was ready to move on and the organization needed a new direction. Tim was succeeded by Alberto Mendoza, who served as President & CEO from 2007 to 2009. With the departure of Alberto, the decision was made to start the search for a new leader, and they found one in 2010: Dr. Joe Lyou, our current President & CEO. I’ll leave it at that for now, but I hope you’ll stay tuned for our next and final installment where I finally get to tell you all about our most recent accomplishments and what an amazing organization we’ve become.